After her son returned from his second tour in Iraq, Shari Duval of Ponte Vedra, Florida came face-to-face with the devastating reality of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“My son, who is a veteran K9 police officer, worked as a bomb-dog handler for the U.S. army and returned with severe PTSD,” she says. “He looked the same, he’d lost some weight—but it was like the lights were on with nobody home. He was just a shell inside; he had lost all emotion, he was quiet … and then he began isolating. We couldn’t get him out of the house. He started drinking—and this was a kid who never drank. I honestly didn’t know what to do for him.”

Seeking a way to alleviate some of her son’s suffering by drawing on his love for and background working with dogs, Duval embarked on two years of research into canine assistance for PTSD, eventually concluding that the best way to help her son—and others like him—was to start a non-profit organization that would train and give service canines to warriors in order to help them return to civilian life with dignity and independence.

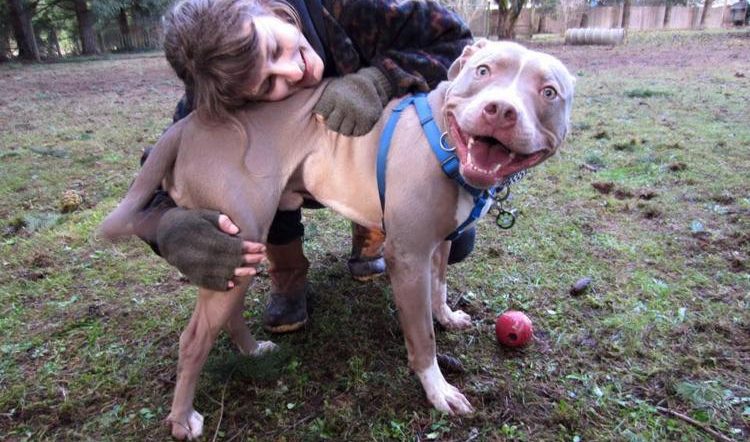

2010 saw Duval’s dream come to fruition with the birth of K9s For Warriors. Within the year, her organization had achieved non-profit status. “We’re dedicated to providing service canines to our warriors suffering from PTSD and/or traumatic brain injury … as a result of military service post 9/11,” Duval explains. “Our goal is to give ‘a new leash on life’ to rescue dogs and military heroes.” The “rescue dog” aspect is an important one—at first, Duval believed she’d need to raise and train purebred dogs in order to do this important work. But she soon came to the conclusion that there were “too many excellent, beautiful dogs in shelters that need good homes” and that, with help from a team of trainers and evaluators, “we could save some of these dogs’ lives while simultaneously tackling the issue of PTSD.” Today, K9s For Warriors’ roster of dogs is gleaned almost exclusively from shelters across the U.S. Most of the animals, says Duval, are Labrador Retriever or Golden Retriever mixes—unfortunately, the organization’s insurance coverage prohibits it from including “bully breed” dogs. Beyond breed, Duval says, “Not all dogs are capable of working. They need to have the right personality and temperament—we’re looking for smart, even-keeled animals who are relatively low maintenance and eager to learn.” Size, too, matters, and retrievers are ideal in that many of the warriors in the program have mobility issues and wouldn’t do well with a smaller dog. “We only accept dogs under two years of age and, once they’re pulled or donated, we have them medically checked by our own vet for any potential issues like hip dysplasia,” Duval explains. “The last thing we want is to give a veteran a dog and have it come down with a problem that would prohibit it from working.” The dogs are then kept under evaluation for 30 days to “see how they get along with other dogs, people, children, noises, cars, public places … the entire process lasts between 30 and 40 days before a dog is accepted into the program.”

And what becomes of an animal that falls short? Happily, K9s For Warriors has never been forced to return an animal to a shelter. Rather, dogs deemed “not fit” to be service animals are placed as pets with loving families. “It’s about a 10 percent wash-out rate,” says Duval. “But we’re really proud of the fact that, of [the near] 200 dogs we’ve matched with warriors to date, we’ve only made two mistakes where the pair just didn’t bond.” That’s because, as thorough as K9s is about choosing the right animals to enter its program, the application process for people is just as thorough, to ensure the wellbeing and success of everyone involved. “We conduct many, many conversations with them—we even go so far as to have them submit pictures and videos of their home environment, so that we can take into account whether they live in an apartment or house, have a yard, have children or other pets,” she says. “We determine how mobile each warrior is, as well as what they like to do. If a veteran likes to go kayaking or hiking, we want to make sure we pair him with a dog that can do these activities.” Duval stresses the fact, however, that “these are service dogs trained with specific skills—they’re not therapy or companion dogs. Some are taught to pick things up, others learn retrieval or how to open and close doors. A common issue associated with veterans with PTSD is a strong dislike of being approached from the front or back; it really puts them on guard. Our dogs are taught to cover in the back and block in front, to alleviate this.” One inherent skill that, she says, a large portion of dogs in the program seem to instinctively possess (that is, it’s not a taught behaviour), is “waking their warriors up from horrific nightmares and flashbacks. The dogs will lick their faces or pull on them to bring them back to reality—that just comes from the bond of being with them.” Considering the commonly cited statistic that 22 veterans a day are lost to suicide, Duval says the biggest overall benefit of the K9s For Warriors program is, “We’re saving their lives. These dogs are saving lives. The dogs take the place of medication, and give veterans a reason to stop isolating themselves, to get out there and to live.”

See more at: http://moderndogmagazine.com/articles/how-one-organization-saving-lives-war-veterans-and-shelter-dogs/89395